The “Invisible Tax” on Solana

Years ago, the article “Payment for Order Flow on Solana” exposed a shadowy aspect of Solana’s fee market, igniting widespread discussion across English-language crypto Twitter.

Payment for Order Flow (PFOF) is a well-established model in traditional finance. Robinhood famously used PFOF to pioneer “zero-commission trading,” quickly outpacing legacy brokerages. This approach not only generated substantial profits for Robinhood but also forced industry leaders like Charles Schwab and E-Trade to adopt similar strategies, fundamentally reshaping the U.S. retail brokerage landscape.

In 2021 alone, Robinhood earned nearly $1 billion in PFOF revenue, accounting for roughly half its total annual income. Even as late as 2025, Robinhood’s quarterly PFOF revenue still reached hundreds of millions of dollars, underscoring the extraordinary profitability of this business model.

Market makers in traditional finance strongly prefer retail order flow. The reason is straightforward: retail orders are considered “non-toxic”—they’re usually driven by emotion or immediate need and don’t reflect precise forecasts of future price movements. By absorbing these orders, market makers can reliably capture the bid-ask spread without the risk of trading against informed institutional players.

To capitalize on this, brokerages such as Robinhood package retail order flow and sell it in bulk to market-making giants like Citadel, collecting hefty rebates in the process.

Regulatory oversight in traditional finance offers retail investors some protection. The SEC’s Regulation NMS requires that even bundled orders must be executed at prices no worse than the prevailing market best.

In contrast, the unregulated on-chain environment enables applications to exploit information asymmetry. They prompt users to pay priority fees and tips far above actual network requirements, quietly pocketing the excess. In effect, this practice levies a steep “invisible tax” on unsuspecting users.

Monetizing User Flow

For applications with significant control over user access points, monetization strategies are far more sophisticated than most realize.

Front-end applications and wallets decide where user transactions are sent, how they are executed, and even how quickly they reach the chain. Every stage in a transaction’s lifecycle presents an opportunity to extract value from the user.

Selling User Access to Market Makers

Just as Robinhood does, Solana applications can sell “access rights” to market makers.

The Request for Quote (RFQ) model exemplifies this approach. Unlike traditional AMMs, RFQ allows users or applications to request quotes and trade directly with specific market makers. On Solana, aggregators like Jupiter have already implemented this model (JupiterZ). Here, applications can charge market makers a connection fee or, more directly, bundle and sell retail order flow. As on-chain spreads continue to narrow, this “user brokerage” model is likely to become even more prevalent.

Additionally, alliances are emerging between DEXs and aggregators. Proprietary AMMs and DEXs depend heavily on aggregator-driven traffic, while aggregators have the leverage to charge liquidity providers and rebate a portion of profits to front-end applications.

For example, when the Phantom wallet routes a user’s trade to Jupiter, underlying liquidity providers like HumidiFi or Meteora may pay Jupiter for the right to execute the trade. Jupiter, after collecting this “channel fee,” then shares part of it with Phantom.

While this arrangement is not publicly confirmed, the author believes that, given financial incentives, such revenue-sharing practices are virtually inevitable within the industry.

Predatory Market Orders

When a user clicks “Confirm” and signs a transaction in their wallet, it essentially creates a market order with a slippage parameter.

Applications have two main options for handling these orders:

Constructive: Sell the resulting “backrun” (trailing arbitrage) opportunity to professional trading firms and split the profits. Backrun refers to a scenario where a user’s buy order on DEX1 pushes up the token price, and an arbitrage bot immediately buys on DEX2 within the same block (without affecting the user’s execution price on DEX1), then sells on DEX1.

Exploitative: Collaborate with sandwich attackers to target their own users, artificially inflating execution prices.

Even when taking the constructive path, applications may not act in users’ best interests. To maximize backrun value, they might intentionally delay transaction submission. Driven by profit, they could also route users to low-liquidity pools, creating larger price swings and more arbitrage opportunities.

Reports indicate that some prominent Solana front-end applications engage in these practices.

Who Takes Your Tips?

While the above strategies involve technical complexity, manipulation of “transaction fees” is often blatant.

On Solana, user fees are divided into two components:

- Priority Fee: A protocol-level fee paid directly to validators.

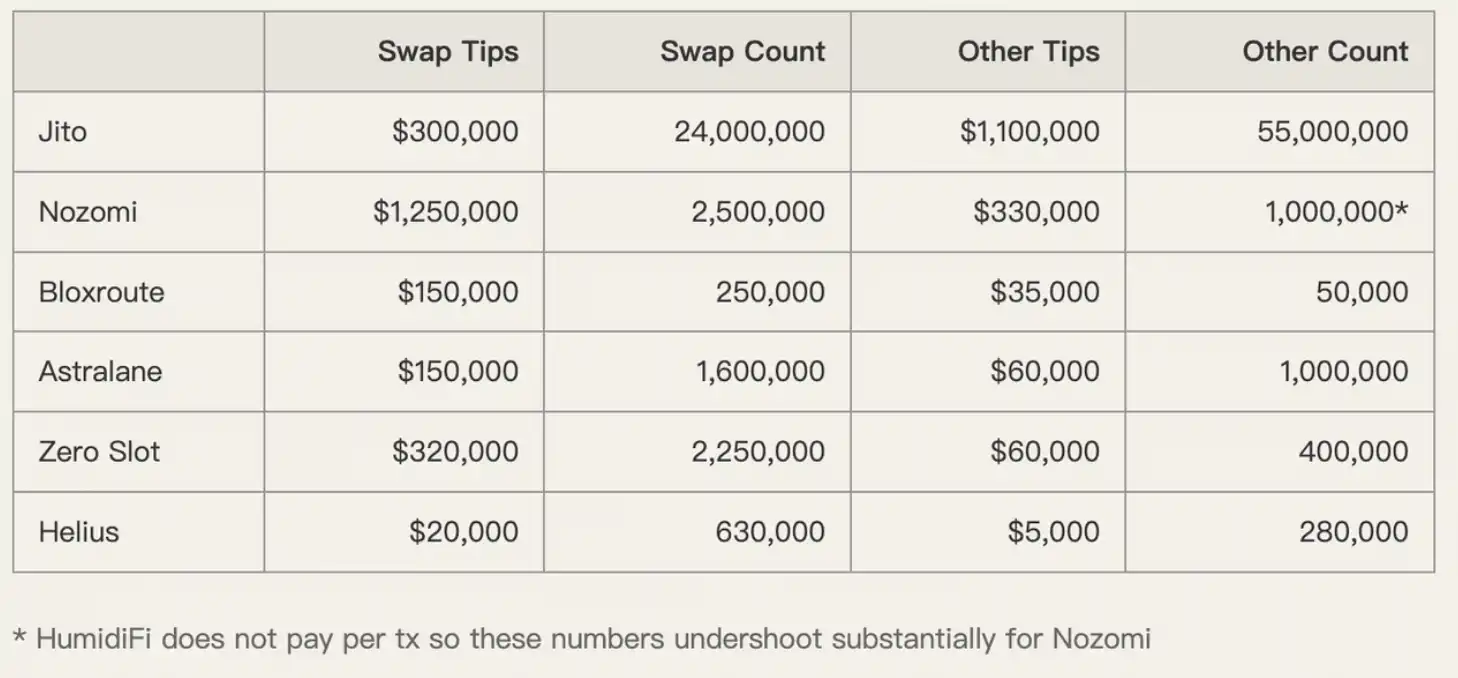

- Transaction Tip: A payment in SOL to any address, typically a “landing service provider” like Jito. These providers then decide how much to share with validators and how much to rebate to the application.

Why use landing service providers? During periods of network congestion, standard transaction broadcasts are likely to fail. Landing service providers act as “VIP channels,” optimizing routes and promising users successful transaction inclusion.

Solana’s complex builder market and fragmented routing system have fostered this role, creating prime rent-seeking opportunities for applications. Applications often prompt users to pay high tips for “guaranteed inclusion,” then share the premium with landing service providers.

Transaction Flow and Fee Landscape

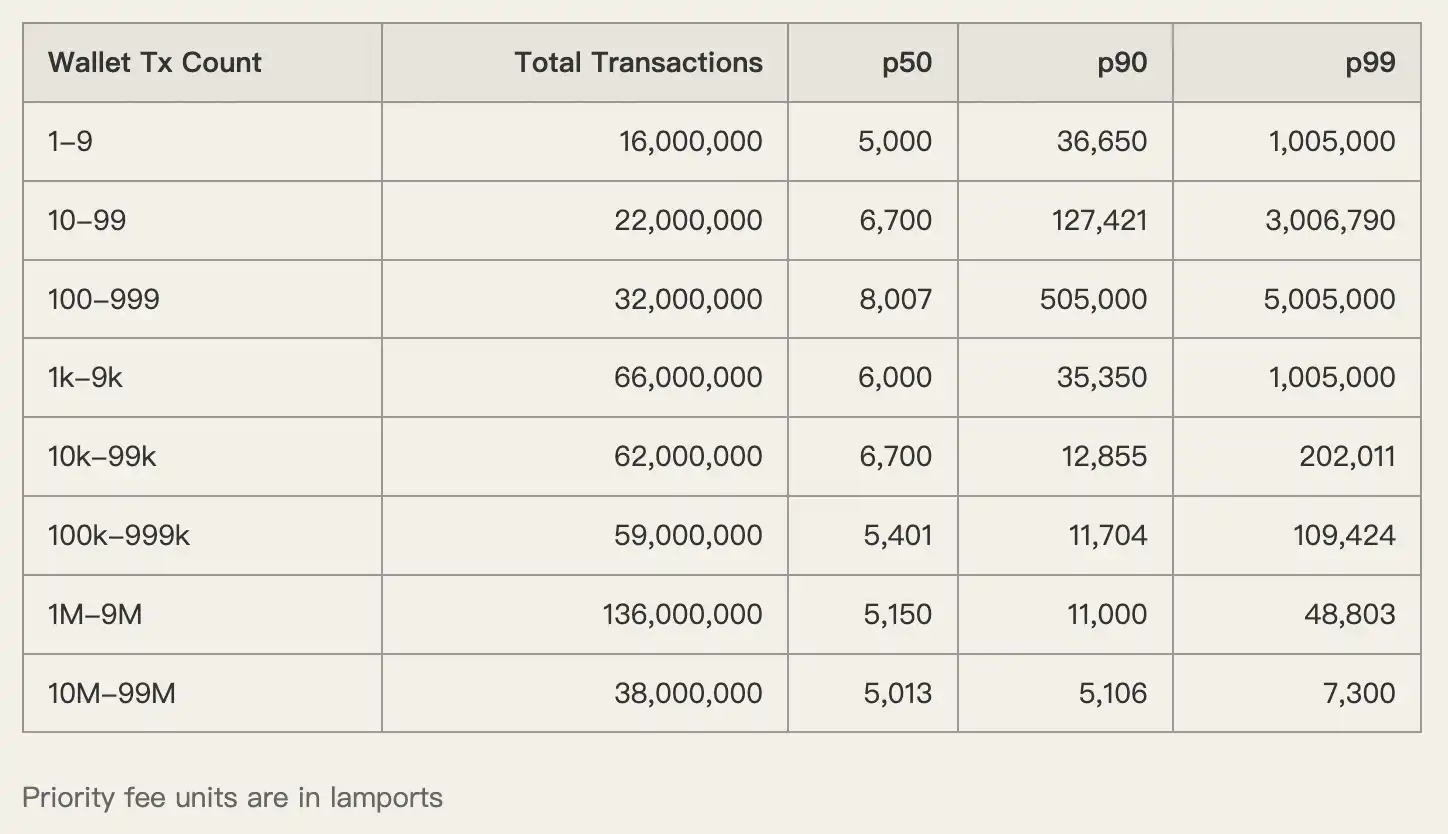

Consider the data: Between December 1 and 8, 2025, Solana processed 450 million transactions network-wide.

Jito’s landing service handled 80 million of these, dominating with a 93.5% builder market share. Most of these transactions involved swaps, oracle updates, and market-making operations.

In this high-volume environment, users often pay steep fees hoping for faster transaction inclusion. But are those fees truly necessary?

Not always. Data shows that low-activity wallets—primarily retail users—pay disproportionately high priority fees. Since blocks weren’t full at the time, these users were clearly overcharged.

Applications exploit users’ fear of transaction failure, encouraging them to set excessive tips. Through agreements with landing service providers, they capture this premium.

Axiom: The Negative Example

To illustrate this “extraction” model, the author conducted a case study on Axiom, one of Solana’s leading applications.

Axiom generated the highest transaction fees on the network, not just because of its large user base, but also due to aggressive fee practices.

Data shows Axiom users paid a median (p50) priority fee of 1,005,000 lamports. In comparison, high-frequency trading wallets paid only 5,000–6,000 lamports—a 200-fold difference.

The same applies to tips.

Axiom users paid tips on landing services like Nozomi and Zero Slot far above the market average. The application exploited users’ sensitivity to speed, double-charging them without any negative feedback.

The author bluntly concludes, “The vast majority of transaction fees paid by Axiom users ultimately end up in the Axiom team’s pockets.”

Reclaiming Fee Pricing Power

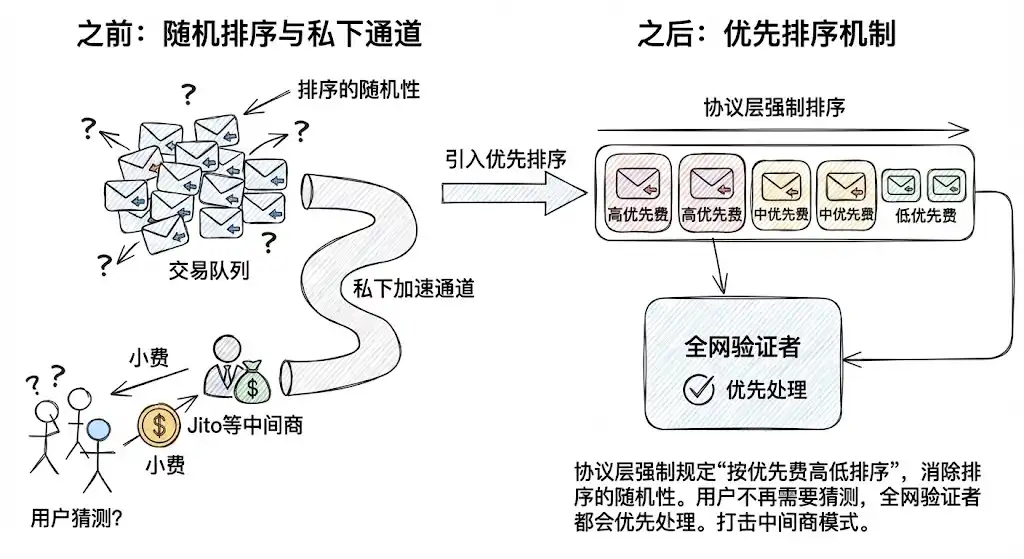

Severe misalignment between user and application incentives is the root cause of today’s challenges. Users don’t know what a fair fee is, and applications have every incentive to keep them in the dark.

To resolve this, we must reform the underlying market structure. The anticipated introduction of Multiple Concurrent Proposers (MCP), Priority Ordering, and a dynamic base fee mechanism on Solana—expected around 2026—may provide a solution.

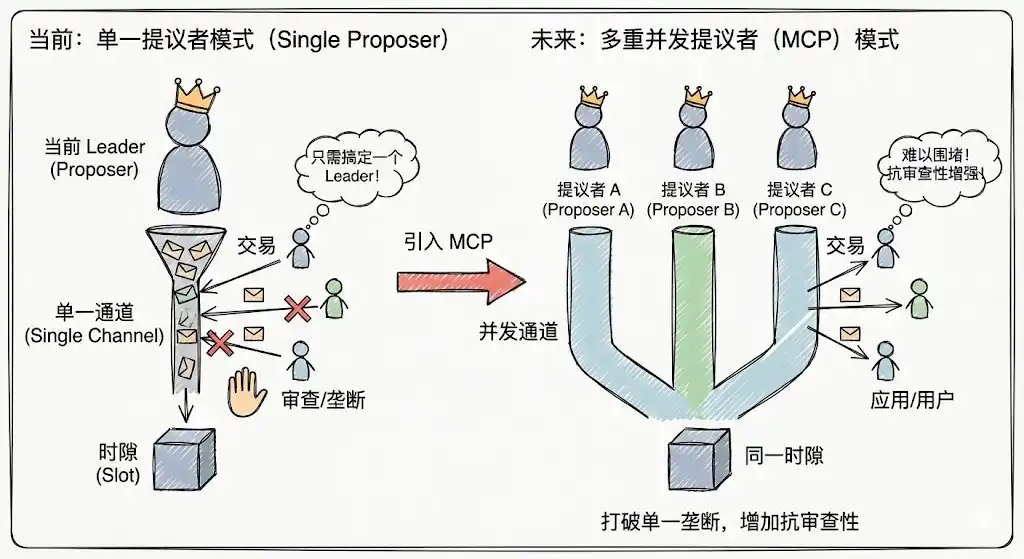

Multiple Concurrent Proposers (MCP)

Solana’s current single-proposer model is vulnerable to temporary monopolies, where applications can gain control by influencing the current leader. MCP introduces multiple proposers working in parallel for each slot, significantly increasing the cost of attacks and monopolies, boosting censorship resistance, and making it much harder for applications to corner users by controlling a single node.

Priority Ordering

By enforcing protocol-level sorting by priority fee, randomness (jitter) in transaction ordering is eliminated. This reduces users’ reliance on private acceleration channels like Jito for guaranteed inclusion. For standard transactions, users no longer need to guess tip amounts—simply paying the protocol ensures validators prioritize their transactions according to deterministic rules.

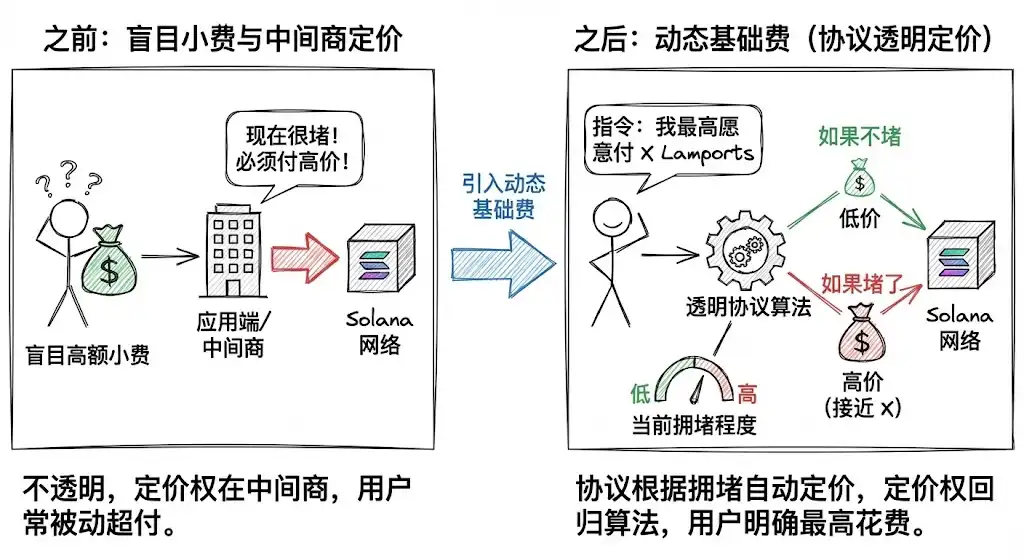

Dynamic Base Fee

This is the most critical reform. Solana is working to introduce a dynamic base fee model similar to Ethereum’s.

Users will no longer blindly tip; instead, they’ll instruct the protocol, “I am willing to pay up to X lamports for this transaction to be included.”

The protocol will set fees automatically based on real-time network congestion. If the network isn’t congested, only a low fee is charged; if it is, the fee increases accordingly. This mechanism shifts pricing power from applications and intermediaries to a transparent protocol algorithm.

Memecoins brought explosive growth to Solana, but also left it with a culture of speculative profit-seeking. For Solana to realize the vision of ICM, it must prevent applications controlling user traffic and protocols controlling infrastructure from colluding unchecked.

As the saying goes, “Clean house before inviting guests.” Only by upgrading the technical architecture, eliminating rent-seeking, and building a fair, transparent market structure that prioritizes user welfare can Solana truly compete with and integrate into the traditional financial system.

Statement:

- This article is republished from [BlockBeats], with copyright belonging to the original author [SpecialistXBT]. For republication concerns, contact the Gate Learn team for prompt resolution following applicable procedures.

- Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed are solely those of the author and do not constitute investment advice.

- Other language versions are translated by the Gate Learn team. Unless Gate is referenced, translated articles may not be copied, distributed, or plagiarized.

Related Articles

The Future of Cross-Chain Bridges: Full-Chain Interoperability Becomes Inevitable, Liquidity Bridges Will Decline

Solana Need L2s And Appchains?

Sui: How are users leveraging its speed, security, & scalability?

Navigating the Zero Knowledge Landscape

What is Tronscan and How Can You Use it in 2025?